|

Life with the Highway

40 years of cultural change

story and photos by Karen West

part three of three | << part one | << part two

Forty years ago, on Sept. 2, 1972, the North Cascades Highway opened and forever changed the culture of what had been a dead-end rural valley where everybody pretty much knew everybody else and people worked hard for what little they had. It was a day to celebrate – an 80-year-old dream come true.

There never had been much talk about what, aside from tourists, the highway would bring into the valley. And Winthrop was all gussied up as a Western theme-town-in-waiting for them. But even those hopeful about a boost to the local economy could never have foreseen how a booming national economy, the internet/dot-com revolution and an explosion in the number of urban-dwelling weekend athletes would conspire to change the Methow Valley.

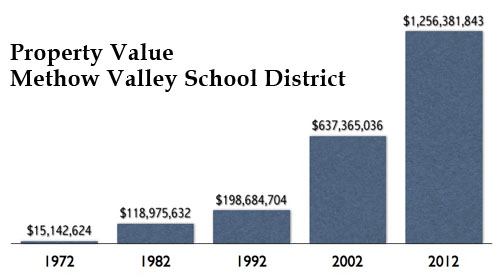

Total tax-assessment value for property within the the Methow Valley School District starting in 1972 when the North Cascades Highway opened. Source: Scott Furman, Okanogan County Assessor

If you could choose only one statistic to show how dramatic the last 40 years of change has been, it would have to be this one from Okanogan County Assessor Scott Furman: Property within the Methow Valley School District boundaries was valued at slightly more than $15 million in 1972; today it's value is more than $1 billion.

Most locals said it took 15 to 20 years from the time the highway opened for the most visible cultural shifts to happen. But there were some early, some would say ominous, signs they were coming.

“The first thing that happened was people came [bought property] and put locks on gates and posted ‘No Trespassing’ signs. That was our first clue,” said Donna Filer Schulz of Twisp, whose grandfather settled here in 1888.

You have to understand that nobody locked their doors before the highway opened, let alone their gates.

Schulz related to Grist a conversation she had one day at the Methow Valley Community Center, where she is a board member. The only valley native in the group, she was asked why newcomers still aren’t accepted by some of the old families.

Donna Filer Schulz at the recent Twisp School reunion. She has third-generation valley roots but moved away and returned after 30 years to find some remarkable changes.

“You took our freedom away,” she told them. Asked to elaborate, Schulz said, “Our freedom was the whole valley was ours. We could go anywhere, do anything. It was ours to use. There were no restrictions, even on the forest... Our rule had always been: Close the gate behind you... We lived on an honor system.”

Howard Brewer, who grew up in Winthrop and married a Twisp girl – back when that was the local version of intermarriage – said he stopped deer hunting the year he hiked miles into his favorite spot only to find a house and a fence with a No Trespassing sign. “There was a road in there. If I’d of known that, I would have driven in,” he said.

The second sign of change, said Schulz, was having to get permits and follow rules to use the outdoors. When Schulz was young, she said, “We could take our horses up in the hills, get off and drop the reins. The horses would graze. We’d have our little fire, our food and look out at great views.”

She also talked about going to the Sunny M Dude Ranch outside Winthrop. “For locals, it wasn’t a tourist thing at all. We had our rodeos up there. Anytime you wanted to ride a horse you just went there and did it. No cost.”

“Because we were so poor, you could hardly leave the valley,” Schulz said. “So for people to have money to come here or play here was the last thing on our minds.” She marvels at the amount of money people now spend on play. “We made our own skis. We made our own fun.” To think about tourists coming to the Methow Valley “for the beauty” was not something locals thought about either, she added. When the Wagner lumber mill in Twisp closed in 1984, “I think we all thought we were going to be a ghost town.”

But by the 1980s there was plenty of activity fueling change in the upper valley near Mazama. Plans were proceeding for a downhill ski area at Sandy Butte and an all-year Early Winters Resort, complete with golf course. “Real estate was selling like hot cakes in the upper valley and tourism was growing,” wrote Doug Devin, author of “Mazama The Past 125 Years.” Devin, an avid downhill skier, and others, saw the resort as a way to create local jobs and a sustainable tourist-based economy.

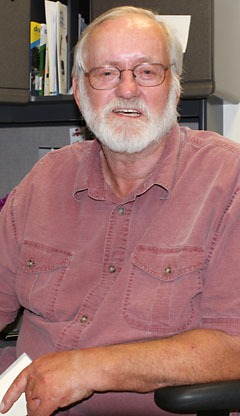

Howard Brewer, who quit hunting after the "No Trespassing" signs went up. He'll celebrate his 90th birthday on Sept. 4.

Property Prices Rise

There was a lot of real estate speculation tied to the proposed ski resort at Sandy Butte, said Furman, the county assessor. The plan eventually collapsed after more than two decades of legal battles and a changing cast of characters. But part of its legacy was that the upper Methow was subject to more sophisticated land use planning than anywhere else in the county. And the media attention, especially from urban news outlets, had boosted the valley’s image as a beautiful place for outdoor recreation, one friendly to “environmentalists” like those credited with--or blamed for--defeating the ski area.

The ski area proposal brought a major culture shift. Many of those who bought property from the old-timers were from the Seattle area, or places like Aspen, Colo., which already was a downhill ski destination. The new owners tended to be more educated than the local population. The valley always had a few people with college educations, Schulz said, but “they were off farms,” which meant they had an understanding of local history and values.

Some new owners were speculators; others planned to stay. As with earlier and later waves of in-migration, some tried valley life and left; others worked themselves into the fabric of the community and stayed. Whatever their goals, the seeds of a recreation-based economy were planted.

The ski area “people were buying property quietly,” said Schulz. “That hurt real bad when we realized they were cheating us.” Not everyone agrees people were cheated. Property prices were low at that time.

“A lot of those old-timers sold their property and then they could buy a place in Wenatchee,” said Bob Ulrich, who owns the pharmacy in Twisp. He supported the ski area. “I was an avid downhill skier.” But in his view, the “highway and ski area hubbub” brought money to people who wouldn’t otherwise have had it. Selling their property “allowed them to be financially independent” as they aged, he said. Some of them moved to Wenatchee to be closer to medical care.

Furman said when plans for the ski area ended, some high priced properties “sat for awhile.” But when “the dot-com thing started,” including the Microsoft wealth, “we saw a huge surge in prices,” he added.

The assessor said he’s watched the Methow change from a rural valley with large parcels of land and farmsteads to a landscape “chopped up into small pieces of property,” many of which have “large custom homes built on them.”

He’s also witnessed a shift in the location of the highest valued property. The Twisp-to-Carlton area used to have a higher value than the Winthrop-to-Mazama corridor but now the upper valley probably accounts for two-thirds of the valley's total property value, he said.

|

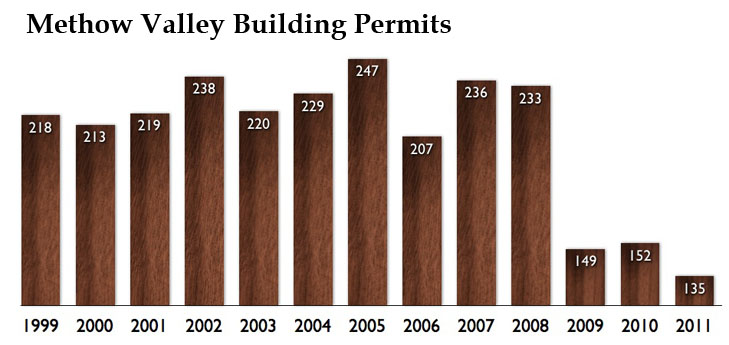

Number of building permits issued for the last 13 years from Methow through Mazama. Statistics for 1972, when the North Cascades Highway opened, are not available. In 1997 the county issued a record 733 building permits, 261 of them for the Methow Valley, which also was a record. Local permits issued for years other than those shown here have not been compiled. Source: Debra Featherly, Okanogan County Building Department

|

There has been a “more than 800 percent increase” in property values for the Methow Valley School District, which extends from Carlton to Mazama, Furman added. That’s a staggering figure given that more than half the students enrolled in the district qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Furman, and others, agree that if the ski resort had been built, its minimum-wage employees would not have been able to afford nearby homes.

By law, assessors must appraise land and structures at their fair market value for property tax purposes. “We raised values 60 percent” in part of the Methow Valley, Furman said, “and really got chewed on... We’re just chasing the tail of the dog most of the time and still getting beat up,” he added.

Outdoor Pursuits

Rosalie Hutson, who grew up here when Mazama really was "the end of the road."

Rosalie Hutson, president of the Methow Valley Senior Center, was born and raised not far from Mazama when it really was “the end of the road.” She told Grist she can’t name one good thing the highway has brought. As for the new people, she said, “They say they come over here for the peace and quiet and then they want to change it.”

Hutson, like Schulz, recalled the days when locals made their own fun. “We used to go dig around in the old dumps at the old homesteads... Now those places are all fences and private property... All the vacant fields are full of houses now... The only people who drove the road before were the people who lived above you,” she said.

As the assistant head of housekeeping at Sun Mountain Lodge for a number of years, Hutson witnessed firsthand the habits of the early tourists who came to cross-country ski. “We used to call them the nuts and berry people,” she said. “They ate nuts and berries and drank tea. They would go into the lounge and order a cup of hot water – free – which would drive the lounge hostess nuts, and bring their own tea bag. And they had their [own] wine. They never tipped.”

She later worked at the Idle-A-While Motel in Twisp, a favorite stopover for snowmobilers. Hutson called them “the steak and beer people.” They were messier than the skiers, she said, but “they were big tippers.”

Today the Methow Valley has the largest cross-country ski trail network in North America, with more than 160 miles of groomed trail. And those who ski here helped pump an estimated $13.5 million into the local economy in 2012, according to figures compiled by the Methow Valley Sport Trail Association. It is a growing number. A 2005 economic study pegged the figure at $8.6 million.

There’s no way to know precisely the total dollars coming into the Methow Valley from those who see it as a destination for outdoor pursuits. But it is obvious to anyone who watches the traffic on Highway 20 through Winthrop that it is the basis of the upper valley economy. For along with those who hunt, fish, snowmobile, ride horses and camp here, there now are droves of motorcycle riders, mountain bikers, climbers, hikers and competitive runners coming as well as the cross-country skiers and non-athlete tourists on short get-aways.

There also are a lot more places for tourists to stay than there were in 1972. Winthrop is set to collect a record amount of money this year from its hotel-motel tax. It wasn’t always so.

Bob Ulrich, owner of Ulrich Pharmacy in Twisp, moved to the valley in 1967.

Native son Bart Northcott, who has early-day Methow settlers on both sides of his family, recalled how few overnight accommodations were available through the late 1970s. His grandparents, and later his parents, owned the Trail’s End Motel in Winthrop, which had six rooms and a mobile home to rent. Northcott said after the highway opened, “People would plan to go on a day ride. They’d get to Winthrop and fall in love with the place and decide to stay overnight.”

If the Trail’s End was full, Northcott said they would make calls. If the local beds were filled, they’d call Okanogan and Omak and then Chelan.“There were times you couldn’t find a room until you got to Wenatchee,” he said. “It was a blessing when The Virginian opened.”

The winters before cross-country skiing became popular were the tough part, Northcott said. The highway was closed for the season. “You stayed open. All the businesses did. But you just about starved to death.”

“We couldn’t afford to get out of the valley,” Schulz said of the pre-highway valley. “People didn’t have gas money.” As for the few tourists who did come, they were called “those people from the coast” who came to fish in the spring and hunt in the fall. “They drank and drank and drank” and showed little respect for local life, she added.

“When hunting season was over this valley shut down,” said Ulrich, who came from Spokane in 1967 and bought the pharmacy. “There was nothing going on until fishing season in the spring.” Ulrich said he “met some real characters.” And like others who’ve lived here at least four decades, Ulrich recalled the wild days when guns were fired in the Antler’s Saloon in Twisp and more than one horse was ridden through Three Fingered Jack’s in Winthrop. “Forty Niners used to be a drunken brawl,” he added, in reference to Winthrop’s annual spring parade and celebration. “Now it’s much more of a family event.”

Diana Hottell, who with her husband, Bill, settled on a small farm up the Twisp River one month before the highway opened, said they started playing music at the Antler’s as soon as they moved here. “Our first hunting season playing there was horrifying,” she said, recalling the drunken brawls and gun-slinging.

The Coming of Second Homes

For Bill Hottell the most significant culture changes came in the 1990s with the “building of trophy homes,” some of which were of the ridge-busting, “skyline intrusion” type. He said a builder once told him that a now-departed owner up the West Chewuch Road had “two complete sets of copper pipes installed” so he could have instant hot water instead of having to wait for the cold to run through a single set of pipes. He said he also heard about a house with five freezers. The people were part-timers who rarely visited yet the house sat there consuming all that energy.

Diana and Bill Hottell settled on a Twisp River farm one month before the highway opened.

By the 1990s, the Methow Valley clearly was starting to reflect the rising wealth of the middle and upper classes that was fueled by a booming stock market, strong national economy and the dot-com revolution.

“Second homes? We’d never heard of second homes,” said Schulz, adding that in this valley most people she knew were struggling to have one home.

“The biggest growth [in Okanogan County] was in the Methow” during the 1990s, said Debra Featherly, who keeps building permit records and compiles the Okanogan County Building Department’s reports. The trend has continued. Her report for 1999 through 2009 shows that 6,187 building permits were issued countywide, about 39 percent of them for the Methow Valley, which the county defines as from Methow through Mazama.

Looked at through the assessor’s lens, it’s clear a lot of those buildings were second homes. When Furman sorts taxpayers by zip code, he finds that “about 51 percent [of Methow Valley property] is owned by people who don’t live there... Those people are treading lightly but contributing pretty heavily,” he said, referring to the property taxes they pay. Imagine, he added, the dramatic “demand for more services” that would happen if all those part-timers suddenly became full-time residents.

Hutson has watched changes in the goods donated to the senior center’s rummage room that parallel the rise of the second-home population. “We’ve got a lot of people with vacation homes over here,” she said. “They can hardly wait for the highway to open [in the spring] so they can shop and bring their stuff in.”

But there is another change in the rummage room that speaks, at least anecdotally, to a growing number of employed newcomers and retirees moving to the valley. Some second homes are becoming primary homes. “In the last 10 years, we’ve really noticed a difference in the stuff we get,” Hutson said. “We get more expensive stuff, a lot more name-brand stuff.”

She said the donors say of their suits and professional wardrobes, “ ‘I moved over here. I don’t need these anymore.’ ” Sometimes there’s no local market for it either, she added. Hutson also is finding that donations for the center’s Christmas and Western sales are more upscale than they used to be.

Working newcomers often are here because the Internet allows them to work from anywhere. One of the most dramatic examples is the Bear Fight Institute located in the upper Rendevous, which hosts scientists from all over the world. The institute’s computers are linked to the National Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which allows them to monitor space exploration projects from the Methow Valley. No professional wardrobe required.

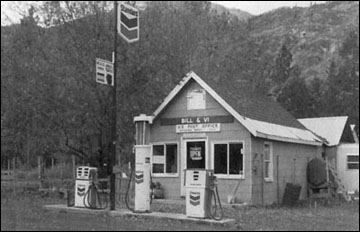

The Mazama store in the late 1960s, before the highway opened. Photo courtesy Shafer Museum The Mazama store in the late 1960s, before the highway opened. Photo courtesy Shafer Museum |

|

The Mazama store now. Only the old gas pump remains from the earlier version. The Mazama store now. Only the old gas pump remains from the earlier version. |

Everyday Life

Schulz may sound nostalgic for the days before locked gates and land-use regulations, but she is quick to say she is not bitter about the changes the highway brought. Hers is an unusual perspective. She moved to Cle Elum in 1976 as a single mother with three children, then on to Seattle. She was used to driving roads where everybody waved. She found herself in a racially-diverse urban world where nobody spoke to her – “unless you had a little doggy or a kid. Then people would talk to you.” Socially, it was a struggle, but she learned to adapt.

Schulz returned to the Methow Valley in 2007 to live on family property in Twisp with her second husband, Jim, a retired advertising agency executive with whom she shared life west of the Cascades.

She came “home” after 30 years to a dramatically changed place and she's found she has to adapt again. Some of the social changes still rankle. The newcomers and second-home owners don’t reach out to her generation of valley natives, she said. The newcomers say, “‘You’re who? I’ve never met anybody who was born and raised here.’”

Schulz decided she couldn’t be critical of people without knowing them so she is reaching out. She joined the board of the Methow Valley Community Center – “I didn’t know a soul on the board.” She joined the community theater group, where she knew one person. She still refers to most newcomers, although not all of them, as “they.”

Last winter the community center hosted “Methow Minds,” a two-night event at which a number of people had been invited to speak on a subject of their choice. Schulz and a longtime valley friend who also has long roots here volunteered to help at the door. As they sat at the back of the room, Schulz said she heard speaker after speaker refer to when the Indians were here, and then say something like, “When I came here,” as if local life started when they moved to the valley. She heard no mention of the valley between the time her ancestors came and when the highway opened. She said she turned to her friend and said, “We’ve been eliminated.”

Winthrop before the highway opened and the town was westernized. Photo by Dick Webb, courtesy Shafer Museum. Winthrop before the highway opened and the town was westernized. Photo by Dick Webb, courtesy Shafer Museum.

Diana Hottell was not the only person interviewed for this story who said, “We came and tried to fit in. Now people are coming and they want to change things.” Her example was to recall that she quit going to fundraising events the day she walked through the door of the Winthrop Barn and found the space all decorated. “It was so slick, organized and well done,” she said. “I said, ‘Bellevue!’ and never went to another one. “Fundraising is something that’s totally not [old] Methow... Now it’s become part of the Methow.”

Part of what Schulz and Hottell are alluding to is the style of urban professionals overlaid on a small, rural place. The edges where the two cultures meet aren't always smooth, but the mix inevitably brings change. Schulz gave an example. "There were always people doing art here, but they gave it away. There was no one to buy it. Then came people who wanted to make money from art."

Hottell mentioned, as a positive change, the vibrant entertainment scene that has become part of valley life because so many musicians have moved here. “You felt like you had to go somewhere else to get your entertainment,” Hottell said of her early decades in the valley. “Now the entertainment has come here.”

“From about 1972 to 1990 nothing ever happened here,” added Bill Hottell. “We were the only band in town except for the Cascade Country Boys, two local men who played music at Sam’s Place in Winthrop.” The biggest – and only – musical event each year was the Pine Stump Symphony, a talent show organized by Ron McLean, a local teacher and third generation valley resident. Hottell called him “one of the giants of the valley.”

The Revolution in Retail

Local business people have seen numerous changes over the past decades – bistros and barristas, T-shirt and trinket shops, bakeries and local coffee roasters, antique shops and art galleries, apparel and sports gear stores, spas and fitness centers -- to name a few.

Bart Northcott, who oversaw the change to more fresh produce and organic foods on the Red Apple Market grocery shelves.

Northcott, manager of the Winthrop Red Apple Market for many years, was in charge of dramatic change on the grocery shelves. He said he and former store owner Lyle Walker attended national food shows, so they knew the trend was toward more natural and organic foods and more fresh produce. Local people used to stock up for the winter, he added. “The case-good sales were a big thing. Now it’s changed to more specialty foods.”

“We were lucky to have people come in and ask for things," Northcott said. "That helped us a lot.” He added that the stores here were ahead of a lot of places because of the people coming here. “Even Wenatchee took quite some time to get on the bandwagon.” Still, Northcott said, “I never thought we’d see the day we’d pay $5 for a head of organic lettuce!”

Hank Konrad, owner of Hank’s Market in Twisp, also credits the requests of the people “who come up here for the summer, have two homes and those who come-and-go” for many of the items he stocks today. They also helped make local people more aware of those products, he added.

Konrad moved to the valley along with his brother in 1975 from Grangeville, Idaho. “We had $11,000 and pregnant wives and had to start somewhere,” he said. They purchased a grocery store located where the Confluence Gallery is now. It was a new venture for Konrad, who had worked in the logging industry. He now presides over, among other things, what is advertised as the “largest selection of cheeses in Eastern Washington.”

Bob Ulrich stocks “a lot of different pills” than he did when he bought the pharmacy. He said there was one old doctor and one “young upstart” named Bill Henry when he arrived. Now there are three physicians and a number of nurse practitioners with clinics in Twisp and Winthrop.

“The people who tend to come here have been under the care of big city physicians,” he said. “What they use is different from what we might use here,” which is why his stock has expanded. The other big change is needing to assist the people who come and forget to pack their drugs. “We deal with it every day.”

A man who knows change is a constant in today’s world, Ulrich said, “I just try to enjoy what’s here now. I think it’s a real magical place... People come in and people go out, but for the people who live here, it’s a magical place and it’s still a homey place.”

High-end foods for dogs, cats, livestock and wild birds are among the changes on the Twisp Feed store shelves. This dog food contains free-run chicken and turkey, wild caught fish and whole eggs.

Katrina Auburn, who’s been in the feed store business since 1998 and owner of Twisp Feed and Rental since 2004, said she’s watched her customers change from the old-time farmers and ranchers to a mix that includes an increasing number of “hobby farmers.”

They are “people who want to be self-sufficient and not rely solely on the food truck coming in,” she said. They have small flocks of chickens, for example, not huge flocks to supply the entire valley like in the old days.

Auburn’s family moved to the Methow Valley from the Omak-Okanogan area in the early 1980s. She calls Highway 20 a plus for the economies of Winthrop and Twisp. “We need the stimulation of growth... But for locals who just want to live here in peace, [the changes] can be overwhelming.

Diana Hottell, who became gravely ill soon after settling here, recalled how overwhelmed she was by the community’s generosity. “It was in the valley fabric to know each other and help each other,” she said. “I was ecstatic about my whole life here.” Forty years on, she said, “I love Twisp. It has remained.”

Auburn agrees. “I love the valley,” she said. "I can’t imagine living anywhere else... We have a very tight community. I think it was a tight community [before the highway]... Your survival really depended on your neighbors helping you. Now the whole community wants to help... People want to belong and be part of a community again... The attitude is, ‘We’re here for you.’”

Schulz said she sees a valley come “full circle,” almost like “looking in a mirror.” When her grandparents came here from Texas in 1888, they were looking for tall grass for their cows, good water, land and a place where they could raise their kids. “And that’s what the ones coming now want,” she said. “They want to live off the land. The difference is that they are educated people who also want to teach others... The land was abused and overused but we didn’t know it.”

Yes, she came home after 30 years to find dramatic changes, but some were welcome. “The valley is still here,” she said. “It’s beautiful – greener and more beautiful than when I left” because of all the grasses and crops that have been planted, the near elimination of barnaby and “the restoration of areas devastated by the 1948 flood.”

And, she concluded, now that we have the Internet “We can be in our own little cocoon and in touch with the world.”

9/2/2012

|