|

Expeditionary Learning

Methow Valley Community School

story and photos by Solveig Torvik

comment on this story >>

Deb Jones-Schuler is head of the Methow Valley Community School in Winthrop. The Methow Valley Community School was founded by a group of parents “who wanted something that wasn’t available at the time,” something “more connected to the valley” and its rich array of human and natural resources, says school head Deb Jones-Schuler, who was one of the school’s founding parents.

The learning model they chose was Expeditionary Learning, an approach developed at the Harvard Graduate School of Education with Outward Bound, a partner with the Community School. Nationwide, the expeditionary learning model has been adopted by 165 schools in 29 states.

Ten elementary school students showed up for class when the Methow Valley Community School first opened its doors in 1999 in the basement of the Little Star Montessori School in Winthrop. Today the well-traveled private school (formerly housed at Paco’s Tacos and the Methow Valley Community Center in Twisp and the Ness building in Winthrop) is leasing a cheerful new home for 56 students at 31 West Chewuch Road in Winthrop. The students transfer to Liberty Bell High School after 8th grade.

Community School tuition costs $6,930 a year, and from the outset, the school has struggled with perceptions that it’s elitist, according to Jones-Schuler, who also helped found Room One. “This isn’t just for rich kids,” she says. Nearly 40 percent of the school’s students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the federal measure of poverty; in the Methow Valley School District, the poverty rate is pegged at 50 percent.

Forty percent of the students are from the Twisp area, according to Jones-Schuler, and 35 percent from Winthrop. Two students are from Mazama, and a handful from the Carlton area. The school pays the public school district to transport its students to Liberty Bell High School, where they are picked up by the Community School’s distinctive blue bus.

No one is denied admission for financial reasons, says board president Lincoln Post. This means 65 percent of the students received from 10 to 90 percent tuition assistance in 2011. Asked how many students are paying the full tuition, Jones-Schuler answers: “I can count them on the fingers of one hand.” Of the school’s current $375,000 operating budget, $221,000 comes from tuition. Grants total $65,000 and fund-raising brought in $89,000, she says.

The school is not accredited but is approved by the state, says Jones-Schuler. Curriculum, financial records and student attendance must be filed with the state. The school employs eight teachers, three of whom have advanced degrees in teaching or counseling but not a teaching certificate; five hold Washington State or other teaching certificates. Teacher salaries are “terrible,” says Jones-Schuler, the lowest of any private school in the state and far less than public school teacher salaries in the valley.

“We are crew, not passengers,” is the school’s working motto. Learners are not just passively taken along for the ride, in other words. The school rejects what it terms “the sage on the stage” model in favor of “the guide on the side.”

Math class at the Community School with teacher Linda Kimbrell. Students, left to right: Nate Hirsch, Noah Batson, Leif Portmann-Bown, Kavi Mitchell. As math and humanities teacher Linda Kimbrell explains it, students are expected to assume more responsibility for their own learning than in traditional classrooms. The teacher becomes a “guide” rather than the “director” of the learning, she says. Students are challenged to work out the right answers to academic problems themselves, for example. “They know Linda is not going to give them the answer,” says Post. “She will never give them the answer.”

Rather than being grouped into traditional grades, students are assigned to “crews” for each year’s in-depth learning expeditions. This year the 10 first-graders in the Patterson Crew are focusing on the concept of community. The 17 second and third-graders in the Goat Peak Crew are delving into weather; among their assignments was writing a paper that explained the life-cycle journey of a single raindrop, says Jones-Schuler. The14 fourth and fifth-graders in the Tiffany Crew are deep into geography and plastics. And the 15 sixth, seventh and eighth-graders in the Gardner Crew are embarked on “The Journey of Self Discovery.” Students typically gather in a “morning circle” at the beginning of each day and end with another circle to review that day’s learning.

The school not only mixes age groups for coursework but assigns older students to mentor the younger ones, says Jones-Schuler. There’s math every day at every level and Spanish language and culture once a week for everyone. And parents make a contractual agreement to spend 75 hours per year doing volunteer work at the school, including grunt work such as maintenance and shoveling snow off the roof.

Shay Crandall, left, and Tova Portmann-Bown compare notes during an Expeditionary Learning outing to the Red Apple in Winthrop. Hands-on learning is a strong component of the curriculum and includes such outdoor activities as building a snow shelter or being driven blindfolded to a drop-off location up Elbow Coulee and assigned to find the way to a pre-determined location by a pre-determined time using a compass. As part of that recent outing, students also learned how to manage in an emergency. Indoors, there’s the Locavores Farm-to-Table program and cooking classes; every Monday students eat hot lunch complete with tablecloths and napkins.

Teacher Jake Otto’s fourth and fifth-graders spent the first semester on geography and now are involved in research on the topic: “Plastics: Friend or Foe?” Chemistry, research and writing are the academic skills emphasized in that course. The students will study how plastics are used in science, medicine, food packaging and other applications, as well as the environmental by-products of those uses, Otto says. The students will learn how to research a plastics-related topic of their choosing, then write a research paper and learn how to share the information they’ve learned in a presentation.

“As a teacher in today’s world, you don’t have to give them the information,” says Otto, because information is available everywhere. “We have to teach them how to get it.”

“I feel this model teaches a student how to learn,” says Post of the expeditionary approach. But he adds that it may not be the right fit for parents who believe academic rigor is only to be found in a more traditional approach to learning.

Initially the parents, several of whom had been active as volunteers in the public schools, had hoped to become a “school within a school” under the Methow Valley School District 350 umbrella, says Jones-Schuler. That didn’t happen. And a more recent effort by the Community School to affiliate with the school district was rejected on legal grounds.

“We were looking at building bridges and to build more financial stability for the school,” says Post, who adds that the school has no plans to further pursue affiliation with the district.

Having 56 students choose to attend the Community School means the school district lost about $380,000 this academic year in state per-pupil funding. Even so, all the district’s school board members express support for the school. “I think the Community School is a wonderful asset,” says public school board member Frank Kline. “I think it makes us as a public school work harder. I think competition is good. If there was some way we could work together legally, it would be wonderful.”

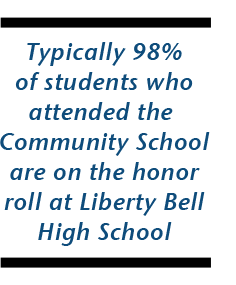

The school tracks its graduates, says Jones-Schuler. Typically 98 percent of students who attended the Community School are on the academic honor roll at Liberty Bell High School; at the moment 100 percent are. Community School students report that “they need to work through the subject matter faster (at Liberty Bell) than they do here,” she says. “We go really deep into a subject.”

Of the eight students who graduated as sixth graders from the Community School in 2002, two have completed college degrees and have joined the work force while six are nearing completion of their undergraduate work at the University of London, Lewis and Clark College and University of Washington, among other schools. Younger alumni are attending such schools as Eastern Washington University, Gonzaga, University of Utah and Western Washington University, according to Jones-Schuler.

“They’re doing a great job,” says Methow Valley School District’s board president and long-time educator, Mary Anne Quigley. She says she’s spent a good deal of time at the Community School and credits it with inspiring some positive changes in the public school classrooms. The Community School was an early adopter of experiential-based learning, she notes, and she adds that over time there’s been a two-way exchange that’s improved teaching methods in both the private and public schools.

But Quigley rejects the perception that there’s a marked difference in the approach to teaching and learning at the Community School and the public schools. “That’s not my impression at all,” she says.

2/9/2012

|